Smart Operations v2.0

Thomas C. Fountain

Managing Member, TCF & Associates, LLC

An updated vision for business transformation which delivers a digitally enabled business operating model based on optimizing business response to actual and predicted events

Executive Summary

This document presents an updated vision for Smart Operations, a digitally-enabled business operating model that optimizes business responses to actual and predicted events through intelligent processes, AI, and advanced analytics. It builds on a 2003 foundational vision that emphasized near real-time decision-making and process optimization, integrating people, processes, and technology to achieve hyper-competitiveness in dynamic markets.

Introduction and Evolution of Smart Operations

Smart Operations originated from experiences at General Electric and Honeywell, combining Six Sigma, Lean principles, and early digital technologies to improve speed, cost, and quality in business processes. The original vision focused on automating well-defined process steps and leveraging analytics for decision support. Over two decades, advances in cloud computing, AI (including machine learning and generative AI), and cybersecurity have expanded the potential of Smart Operations, necessitating a refreshed vision—Smart Operations v2.0—that fully exploits these technologies while addressing business and people change management challenges.

Core Concepts of Smart Operations v2.0

Smart Operations v2.0 retains the original principles of optimizing business execution but now incorporates AI and next-generation capabilities to vastly expand the solution space for optimization. The approach is evolutionary, enabling incremental benefits and trust-building through phased investments. The model emphasizes a “Sense-Analyze-Optimize-Respond” cycle inspired by the OODA loop, enhanced by the proliferation of digital sensors and digital twins that provide rich environmental and operational data for predictive and prescriptive analytics.

Smart Operations Build-Out: Five Key Steps

- Understanding Processes: Deeply map and characterize current business processes, capturing both explicit and tacit knowledge, measuring performance at task and end-to-end levels, and benchmarking against entitlement and target capability levels to identify improvement strategies.

- Classic Automation: Apply mature automation techniques to low-complexity, low-variability process tasks, prioritizing improvements by ROI and impact on overall process performance.

- Task-specific Agents: Deploy AI-powered agents to handle more complex and variable tasks, leveraging machine learning and generative AI. Integrate these agents into a unified framework to enable consistent development and operations.

- Agentic Capabilities: Enable collections of agents to interoperate and optimize collectively across broader contexts, achieving global optimization beyond local task improvements. This includes modeling complex business problems such as demand forecasting, inventory management, and logistics optimization, culminating in execution orchestration across internal and external resources.

- Continuous Improvement: Continuously enhance agent capabilities, data acquisition, partner engagement, and orchestration reach to expand the solution space and improve business outcomes.

Business Transformation Considerations

The document identifies contemporary challenges such as accelerated product cycles, complex supply chains, geopolitical risks, and ESG considerations, illustrating how Smart Operations can address these through enhanced modeling, prediction, and optimization. It also highlights opportunities like sovereign interests, AI/technology advances, and unprecedented data access, which Smart Operations can leverage for competitive advantage.

Core Transformation Strategies

A successful transformation requires clear financial objectives, business strategy mapping, competency assessment, and a thorough understanding of existing applications, analytics, and enterprise data. Business capability and process design/improvements are essential, including specific plans for process, people, and technology improvements all supported by a robust communications infrastructure to maintain organizational alignment and trust.

Key Constituencies in Transformation

Five key groups are identified: Senior Business Leadership, Deal Team & Investment Professionals (especially in Private Equity contexts), Functional Leaders & Operating Partners (Again for PE situations), IT Teams, and Technology & Service Providers. Each plays a vital role in sponsoring, designing, executing, and sustaining the transformation, with distinct contributions and benefits.

The Future of Work

With the introduction of sophisticated AI and other analytical technologies Organizations must anticipate the impact on organizational design and individual responsibilities. A segmentation approach is introduced which characterize a High Volume / Low Complexity set of activities well served by “automation” capabilities; a Low Volume / High Complexity segment where advanced analytics and AI can outperform humans in speed and analytical depth; and finally a third segment where humans lead the critical responsibilities for setting vision, goals, boundaries, company principles, and provide general oversight for situations where a machine-only scenario does not hold up well for first-of-kind and unanticipated situations.

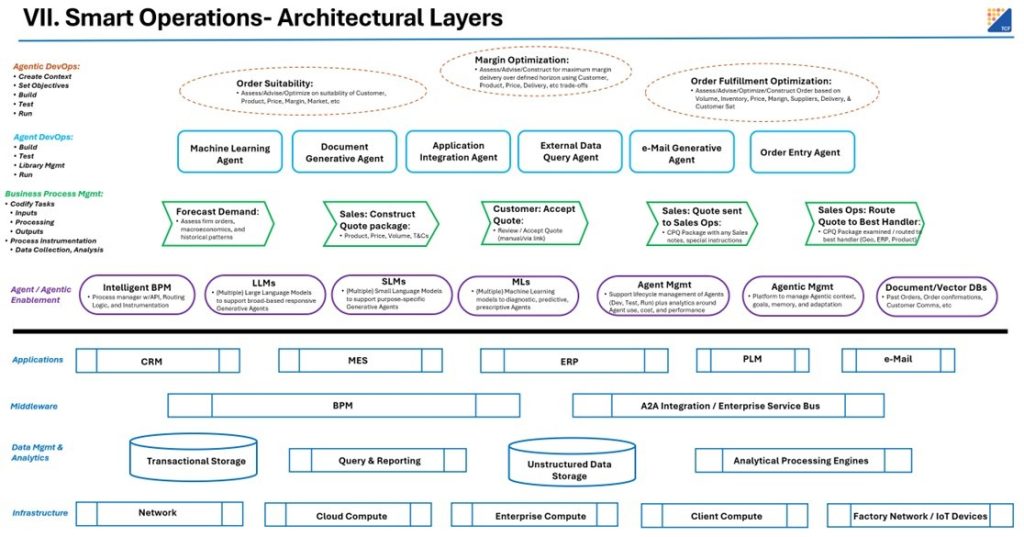

Architectural Layers

The architecture is layered into “below the line” and “above the line” components. Below the line includes traditional enterprise Applications, Infrastructure, Analytics & Data Management, and Middleware. Above the line introduces dynamic, modular layers for Agent and Agentic enablement, Intelligent Business Process Management, Classic Automation, Agent-based Execution Management, and Agentic Execution Management leveraging Context and Communications Management. This layered approach supports speed, adaptability, and scalability in business operations and flexibility for a rapidly evolving technology landscape.

Solution Operating Model

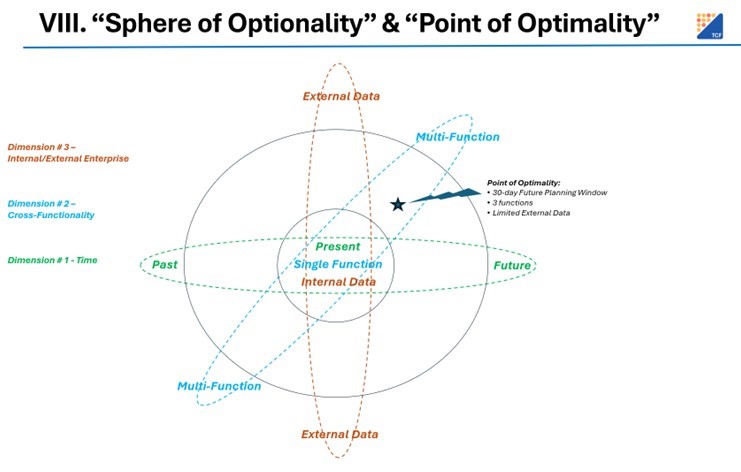

The model conceptualizes a “Sphere of Optionality” within which data is analyzed and business decisions are made to activate optimization strategies. Three dimensions are discussed: Time (past, present, future), Cross-Functionality (integrating multiple business functions), and Internal/External (data and processes inside and outside the enterprise). The goal is to find a “Point of Optimality” within this sphere that maximizes business outcomes. The system must support dynamic re-optimization triggered by significant changes in inputs or constraints, balancing responsiveness with practical considerations like human action-taker stability.

Business and People Change Management

A balanced approach segments work into three categories: high volume, low complexity tasks suited for automation; low volume, high complexity tasks suited for machine learning and other high-powered analytical techniques; and human-centric strategy, vision, and compliance set of tasks that retain critical human judgment and ethical oversight. The document emphasizes proactive organizational development, skills assessment, learning path design, and transparent communications to prepare the workforce for transformation and foster engagement and trust.

Program Guiding Principles and Operating Model

The transformation program should be modular, with clear roles for diverse constituencies and robust communication both internally and with external partners. It must demonstrate incremental value through phased investments, maintain rigorous program, and change management disciplines, and prioritize people-centric approaches to ensure adoption and success. The program phases include chartering, prioritization, process capability assessment, roadmap development, business case creation, sponsorship, deployment of automation and agentic layers, and continuous performance measurement.

Role of Technology and Service Partners

Given the complexity and scope of Smart Operations transformation, external partners are essential for business consulting, technology strategy and architecture, program and change management, and technology implementation. Partners bring expertise in aligning technology with business strategy, managing multi-phase programs, driving adoption, and delivering measurable business value. Proposed financial models create a low upfront investment approach with gain-sharing arrangements to bootstrap the transformation journey and sustain funding.

Critical Success Factors

The document underscores the importance of clear vision, continuous communication, disciplined program management, robust value measurement, and especially the central role of people in embracing and leveraging new capabilities. These factors are pivotal in achieving a thriving, continuously improving, high-performing enterprise enabled by Smart Operations.

Contents

Section 1: Smart Operations & Strategic Transformation.. 6

1. Introduction – The Genesis and Evolution “Smart Operations” 6

3. Business Transformation Considerations. 17

4. Core Transformation Strategies. 21

Section 2: Architecture & Operating Model of Smart Operations. 32

8. Solution Operating Model 39

Section 3: Transformation Programmatics. 42

9. Business Change Management 42

10. People Change Management 44

11. Program Guiding Principles. 45

12. Program Operating Model 46

14. Technology & Services Partners. 49

15. Financial Resourcing & Partner Engagement 51

16. Identification, Quantification, and Measurement of Business Value. 54

17. Critical Success & Risk Factors. 56

Section 1: Smart Operations & Strategic Transformation

1. Introduction – The Genesis and Evolution “Smart Operations”

In 2003 I published an initial whitepaper outlining a vision called “Smart Operations” – a vision which characterized the transformation of a business which:

- actively built and deployed intelligent business processes

- that leverage the accumulated intelligence of its ecosystem

- to orchestrate the optimal response to actual and predicted events

The heart of this concept was the idea that businesses who could intelligently and optimally make near real-time, optimizing business decisions are positioned to out-execute competition. The concept of having analytics and intelligent process management help guide the execution of a business made-up of people, processes, and various systems (transactional, analytical, and planning) and having those elements amalgamated in a dynamically optimized context would be super competitive in any industry.

The initial formulation of this vision was grounded in part by real-life experiences while employed initially by General Electric and later Honeywell International. At GE, the process capability and improvement disciplines of Six Sigma were broadly adopted and deployed in all GE businesses. The core tenets centered on a deep understanding of current process capability, entitlement, and target performance and provided a robust, data-driven approach to either improving or re-designing processes that were not performing at target levels. At Honeywell, lean principles were added to Six Sigma to root out waste and simplify some of the heavy analytical elements of the full discipline yet deliver similar process improvements. I saw first-hand the significant improvements in speed, cost, and quality of many key processes from on-time product delivery to reducing cycle times for jet engine design and validation. In addition to the core improvements realized, these frameworks rightly included the sustainment or “control” element that was a required part of every project to ensure that performance did not revert to prior bad practices once the project spotlight had faded.

Another formative component of the vision was the emerging discussions from the technology industry leaders of the day about how emerging technology could accelerate product and service design, manufacturing, and delivery. Bill Gates of Microsoft wrote of the “Digital Nervous System” and we recall TV ads where robotic paint sprayers immediately reacted to customer order changes. Hewlett-Packard espoused an “Adaptive Enterprise” strategy where fast compute and analytics would speed decision-making while IBM promoted the concept of “Smarter Planet” where intelligent processes leveraged broad insights. One could successfully argue that none of these concepts were fully realized and further make a case that to successfully transform a business you cannot rely solely on advanced technology. In this paper considerable content will be offered to emphasize the holistic nature of the proposed business transformation journey and the necessary deep interconnectivity between people, processes, and technology.

This original Smart Ops (for short) vision was of grounded in the technology of the early 2000s, namely basic business process management platforms, transactional applications, and increasingly data warehouses and basic query/reporting tools. The overall proposed approach was evolutionary in nature and started with basic process automation. There, early robotic capabilities as we now call them, would automate processes or steps where inputs, outputs, and processing rules were well bounded and relatively easily encoded into a modest set of rules to perform useful work. In any business process it is reasonable to expect a select set of steps where input to output transformation has a manageable degree of complexity and scale. These are ripe candidates for the relatively simpler automation techniques of the day. There is no doubt that meaningful improvements were made in the speed, cost, and/or quality of key processes such as those examples above with even these now rudimentary technologies.

If we fast forward 20 years, the explosion of data, operating complexity, number of suppliers, depth of supply chain, and such has taken us far beyond where those conventional tools would have been applicable. Fortunately, recent advances in cloud computing (low cost, high scale compute), high bandwidth networks, AI (both machine learning and generative AI (to deal with fantastically large data sets and derive intelligence), and cybersecurity have positioned us to pursue the full potential of Smart Ops. We now have the opportunity to respond to today’s business scenarios and capitalize on such tools while ensuring our tech strategy is robust to the ongoing advancements we see coming.

Therefore, we need to refresh the Smart Operations vision to take full advantage of today’s technology and enablers for what I will call Smart Operations v2.0. Note that most of the principles of the original Smart Ops still hold – faster, optimized decision-making, centered against business objectives, while bounded by a set of active constraints, and leveraging the capabilities of Partners, Suppliers, Customers, and of course internal resources. Such an aggregated set of capabilities should position any business for hyper competitiveness. As we look forward, the evolution of tools and platforms, particularly inspired by new AI developments, promise to provide breakthrough capabilities and accelerate activation of such a vision. We will delve into the dynamics of this build-out later in the paper.

We can imagine an evolutionary path being the most reasonable such that businesses can take a smooth investment profile aligned to this broader vision, but which yields incremental benefits which in turn helps bootstrap follow-on projects. This mechanism should offer a lower risk profile, be more easily funded, and critically, would build increasing levels of trust and credibility for the implementation team. Evolutionary approaches are also highly sensible given the current rate of technology introduction (especially in the AI space) as we can take advantage of new developments in turn without wholesale “rip-and-replace” events. We should anticipate, for example, such transformative market offerings including an “Agent” Marketplace” that are full of third-party, ready-to-use and pay-per-use AI agents that can be tapped into specific flows and activities on demand.

While the emerging technology is exciting and empowering, we must ground ourselves in the realities of both business and people change management. Incredible numbers of articles are pouring forth daily predicting or reflecting the impact these new technologies will have on the workforce, the business operating model, and even the nature of work itself. Content within this paper will characterize important considerations and practical steps a business should take to prepare itself and its staff for these opportunistic, sometimes traumatic, and unquestionably dramatic changes on the horizon. If done proactively and thoughtfully, organizations can take a leadership role in structuring change in a positive way and energize its staff to continually adapt and leverage technology for long term professional success.

In addition to optimizing pure business outcomes, we also expect an evolution in how this “Smart Ops” engine is built and operated. While contemplating the ultimate scale and cost of running this construct, we should consciously build in operational approaches that leverage a dynamic mix of self-built, purchased, leased, or pure pay-per-use resources where optimization capabilities determine when and where to use, for example, different agents that have varying cost, performance, and capability profiles best suited to a current unit of work. This is not something that will happen overnight but there are critical enablers that we must consciously construct to enable evolving our agents or agentic capabilities. Businesses will also be well served to rigorously understand their current capabilities in terms of data, business processes, application landscapes, business sponsorship and governance, the capacity to invest, and critically the partnerships that it has in place or can develop to tap into the required expertise, scale and thought leadership.

2. Smart Operations v2.0

As we characterize Smart Operations v2.0 from a vision perspective, much survives from the original concepts. I still foresee optimizing the execution of business, but now deeply enriched by AI and other next generation capabilities that can materially expand the solution space over which we attempt to optimize performance. In the original Smart Operations paper, the contemplation of both short term and long-term decision making was limited by the technology and compute capacity of its day. Now with the advent of public cloud and a host of other new technologies, the computational, integration, and data management boundaries that might have existed 2 decades ago have largely evaporated. That will free us to think about a virtually unconstrained, far-reaching model driven by an understanding of our business and the ability to specify the constraints and decision variables at any point in time that must be considered. As was said two decades ago, businesses must be keen to understand both their internal capabilities and those of its suppliers, customers, and partners – many of which are hyper-specialized and focused in a given area of functionality with leading capabilities and performance.

While the reader is invited to review the original paper and its in-depth examination of the various building blocks and example use cases, it is instructive to summarize the major tenets of the vision and explain practical applications of its multi-faceted offerings.

At its outset, Smart Operations is based on the concept of Sense-and-Respond. This was an early style of thinking that promoted the rapid activation of one or more, typically pre-developed, responses that were selected based on a sensed event detected by a decision-maker or action-taker. With the rise of computer-based sensors and analytical capabilities in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, the opportunity to not only automate specific activities but introduce “intelligence” started appearing in various Use Cases in hopes of improving both the speed and efficacy of the response. Many of the early solution designs centered on simple trigger-based responses where a set of possible responses were considered and one selected in response to a specific sensed variable value or event. As compute power continued to accelerate, both the speed and depth of analyses possible in the loop also grew. That in turn created the opportunity for enhancements in the breadth and depth of decision-making while maintaining the inherent cycle time design target of the process in question. In the original paper, I advocated for the pulling apart of the Sense-Respond pair and the active insertion of Analyze and Optimize steps to demonstrably characterize the dimensions needed to effect the truly best response. I paid homage to the famous “OODA” loop principles of Observe-Orient-Decide-Act comparing a fighter pilots approach to winning a dogfight to modern businesses combatting the myriad of competitive, customer, supplier, and other dynamics all conspiring to challenge business execution.

An exciting additional development over the last two decades is the explosion of digital sensors now deployed across a multitude of physical situations. Sensors that cover acoustic, temperature, vibration, humidity, and many other environmental and physical disciplines have greatly expanded our ability to model and understand our operating environments. This provides and deeply enriches our solution strategy by covering both physical and digital elements of the solution space. In fact, the marrying of digital intelligence to physical/real-world capabilities and activities provides a much more realistic and representative model of how we conduct business. With digital sensors feeding analytical routines that help us detect or even predict a much wider range of events, we greatly improve our ability to optimally respond in real-life executable ways.

A close companion to the explosion of digital sensors is the emergence of sophisticated “digital twins.” These “twins” are in fact virtualized representations of physical members of our environment and are actual models that accurately characterize design, performance, failure modes, and many other aspects of operation. For industrial scenarios, these twins represent a unique opportunity to digitally build, test, operate, and simulate business operations without the necessary investment in physical devices and space. With such models we can more accurately predict performance and failure modes under varying operating conditions, which is invaluable for building a Smart Operations foundation.

At the heart of the Smart Operations philosophy is a simple fact: every ounce of insight and predictability we can extract from both digital and physical operations translates to increased lead time and certainty of forthcoming events, which in turn creates a larger envelope to determine optimizing future actions. That is, actively enabling and building such capabilities will maximize the solution space over which we can consider orchestration (response) alternatives. Increased lead times means we can choose possibly slower but better actions which lead to improved outcomes. Increased certainty means we can consider tighter confidence intervals and improve the convergence of predicted to actual outcomes.

In fact, nearly every new technology development over the last 20 years will, not surprisingly, improve the speed, cost, and quality of the Smart Operations build-out.

Smart Operations Core Elements & Build-Out

It is critical to balance long and short-term perspectives when undertaking the build-out of a transformative strategy like Smart Operations. In the short term when initial skepticism and lack of confidence dominate, it is crucial to engage a core set of individuals who believe in the vision yet are grounded in the practicalities of delivering value to the business. That core team must diligently pursue fundamental elements of any successful team looking to drive true transformation, including:

- listening to leaders, process owners, and front-line employees, taking the time to understand the business problem and the individual’s personal investment in meeting business goals

- capturing and analyzing data to truly understand the dynamics of the opportunity and accurately depict current and target state

- effectively communicating what the team plans to do and the participation required from all constituents

This core team must also quickly realize that they alone will not “fix” the business but rather they must engage up, down and across the organization, to leverage the collective knowledge, skills, and passion of the entire team. More details about business and people change management will be presented later in the paper, but it is worth mentioning here as it is fundamental to every aspect of the Smart Ops build-out.

The first stage of a Smart Operations transformation relies on a foundational belief that business processes are the fundamental unit of business activity. From taking orders, to manufacturing product, to shipping, servicing, and collecting cash, business processes are the blueprint for how a business works. Even highly creative activities like Process R&D or Marketing campaign design live within a business process. Business processes are effectively containers where inputs are applied, activities undertaken, and outputs delivered. With a core focus on the design, operation, measurement, and continuous improvement of these processes, we can communicate intent, assign responsibilities, measure business performance, maintain accountability, and ultimately deliver value to customers. Our journey will start and finish with how effectively we can influence continuous improvement in these processes as a measure of our ability to sustain differentiated competitiveness in the market.

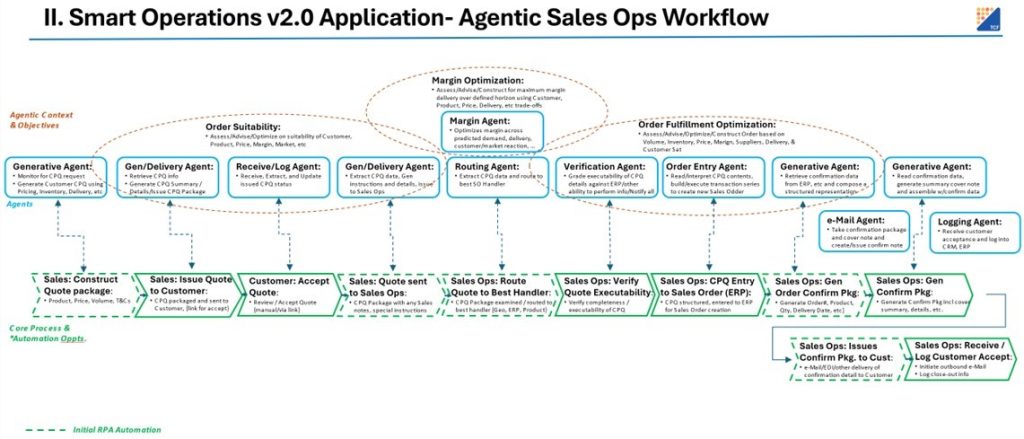

Step 1: Understanding your Processes

With the core focus on business processes in place, the first step of Smart Operations is to embrace the need to deeply understand one’s current processes. To be sure it is very acceptable to focus on one specific business area or operation initially as it could take months or longer to fully map, characterize, and assess the multitude of business processes in a modern enterprise. In our desire to quickly establish a foothold of trust and credibility, it is highly advisable to start small, show quick but meaningful wins, gain more converts as believers in the vision, and move on to other business areas. As such, the core team should deeply map and characterize the initial one or few processes being sure to engage with process owners, designers, and execution staff. Figure 1. represents an example process where Smart Operations has been applied to Sales Operations and will be referred to throughout this section. Taking the time to document the written and unwritten rules, capturing knowledge not in any systems, and faithfully representing how work gets done will be both rewarding and engaging for everyone involved. Like it or not, keeping the truth hidden about errors, poor quality, re-work, and other process incapabilities will quickly destroy any hopes of driving a truly successful transformation.

Figure 1. Application of Smart Operations 2.0 – Agentic Sales Operations

As you map and capture data about speed, cost, and quality you are positioned to properly characterize overall performance. Note that not only must end-to-end performance be characterized, but each step (often called “tasks” today) must also be characterized. Without a step-by-step understanding of your processes, you are rendered powerless to really understand what may be contributing to poor overall performance. Fortunately, there are great tools now available to help you in these activities including process modeling based on transactional data, extracting intrinsic knowledge from workers through AI-structured interviews, etc.

As you complete the analysis of your process you can now effectively baseline performance and critically benchmark it against the required performance levels needed for business success. With that comparative, and an understanding of the process entitlement (max performance potential of the current process design) you can determine your improvement strategy – either remediate the current process or fundamentally re-design for higher potential performance. With this baseline knowledge and a decision on improvement strategy, we can proceed to the next step of the transformation journey and begin the targeted improvement of key process elements until the required performance levels are attained.

Step 2: Classic Automation

As you examine and profile tasks across the collection of activities in an end-to-end process, you will likely see a clustering of tasks based on relative complexity. Specifically, one can classify / categorize tasks by examining the variability within that task’s inputs, activities, and outputs. Its likely that some tasks can be categorized as “low complexity” because there is little variation of those three elements and as such, it is relatively easy to codify a clear set of “business rules” that transform inputs to outputs. In these lower complexity cases, traditional automation techniques can readily be applied. As you refer to Figure 1, such classic automation techniques are represented as dotted process steps across the end-to-end workflow. Such techniques are highly matured and easily specified for a given task. In these cases, businesses are well positioned to deliver solid improvements in speed, cost, and/or quality in the execution of that task. As an aside, do account for reduction in cycle time variability (versus on mean reduction only) as a worthy benefit to note.

Importantly, because you have profiled both task level and end-to-end performance, you will understand the incremental impact on overall performance derived from improving each different task. That detail, combined with clarity of the expense to achieve that improvement, will allow you to develop an optimal sequence of improvement actions. Executing these improvements in the best ROI order will further accelerate overall performance improvement and continue the critical trust and credibility building for the team.

Step 3: Introduction of Task-specific Agents

Having worked through the low complexity/variability process tasks we are poised to attack the more complex/variable tasks in our process. These tasks are the biggest beneficiary of recent AI developments given AI’s general excellence at completing larger scale tasks that require analysis of large data sets and document libraries and/or generating content based on guided modeling. Here we imagine a broad library of Agents accumulating over time, from which we can select and deploy against specific needs within various processes. Some agents will employ Machine Learning (ML) techniques to analyze large data sets and predict customer activity, some will use Generative AI (GenAI) to prepare document summaries or e-Mails to customers, yet others could even collect data and formulate a series of constraints for a downstream optimizer.

In a fashion similar to what was discussed in Step 2, we again profile the highest ROI cases where specific agents are bought/built and deployed against poorly performing process tasks and create measurable improvement for end-to-end process performance. In this step we must also, of course, have built out the ability to develop, test, deploy, manage, and optimize Agents in our environment (more on that later). These Agents are represented in Figure 1 as execution mechanisms paired with each step of the core process. As we successively deploy additional Agents we will see a commensurate rise in overall process performance. Within this step we will also want to begin transitioning the automations from Step 2 into our agent framework to allow them to participate in a cooperative way with all other Agents. Here we can imagine our basic automation steps being wrapped with Agent behaviors to facilitate communications and management. This will prepare our solution for follow-on phases of activity.

Step 4: Introduction of Agentic Capabilities

Having now built out a collection of Agents to perform task-specific duties and accumulated a series of point improvements in our process, we may well seek additional improvements to reach target performance. To break through any current limitations of our current solution we will rely on the old adage from linear programming “the global optimum beats the sum of local optimums.” Translating to our situation, we need to move to a state where collections of Agents can cross-communicate and even cross-optimize behaviors across their collective scope in hopes of finding an even better solution for each instance of the process. Effectively what is happening is by creating context across multiple Agents we are enlarging the solution space across which our collection of agents can trade-off upstream and downstream possible responses to find the overall best response to the current inputs and situation. Such operating context is represented in Figure 1 as the dotted lines encompassing groups of individual Agents.

Creating this context and allowing cross-Agent optimization is the province of “Agentic” behavior. In this realm, collections of Agents, often structured hierarchically, inter-operate to find the best possible outcome against their current tasking. For a business this could include maximizing operating margin by determining what goods to offer, from which warehouses, at which prices, delivered by which carriers for what costs. A complex business problem (opportunity) such as this requires consideration of a vast range of alternatives against a series of inputs and constraints as well as the capability to execute an optimization engine that performs analyses required to identify the best possible outcome that is consistent with those inputs and current state.

Let’s consider the practical application of an Agentic model. In the situation where a retailer wishes to maximize profit over a given time period, we have to consider actual and/or predicted demand and how to most profitably serve that demand. To tackle this opportunity, we first must predict new demand and combine with existing demand to set a baseline for overall Demand to be served. Then we must aggregate available inventory from across a range of warehouses and combine with added supply we could acquire from wholesalers (with what lead times and at what cost) within the time period under consideration. Next, we must gather distribution capabilities of our own delivery fleet and combine with availability and price of 3rd party delivery partners. Finally, we must codify any operating constraints that could curb our plans but must be honored to stay within legal, regulatory, contractual, or other such limits. With all of those inputs in place we have fully characterized the solution space that bounds the selection of our operating decisions that will maximize profit.

The last step of formulating our problem is using yet another Agent to build our “optimization function.” This serves as a description of our business goal and what the optimizer will seek to maximize within the constraints and decisions it can make. This particular Agent would be trained by “reading” past financial statements that characterize all financial elements that are part of the calculation for a firm’s operating margin. The function builder Agent would re-create that formula to consider all appropriate revenue and cost elements, financial adjustments, etc that yield a final margin result.

With the problem formulation (Max function, decision variables, and constraints) we can now call on an “Optimizing” Agent to perform the analysis and deliver the specific decision variable values that serve as the operating plan for our business. These decision variables tell us what to source, from whom, at what cost as well as expected sales, at what prices to what customers in which stores, plus what warehouses will supply product, who will deliver and at what costs. Ultimately the planned business activities and derived revenues and costs deliver the optimized level of income.

The last step of our solution flow is to now activate our optimal plan across the set of action-takers in our operating environment. Initially we would limit such “orchestration” to internal resources over which we have definitive and predictable control. One or more likely a series of “orchestration” agents would send “signals” to either applications (move which inventory between which two warehouses), operators (make 50 units of which product), suppliers (deliver which products to which Customers from which warehouse), and so on to effect activation of our derived operating plan. Orchestration Agents could take many forms from an API call to an application, the creation and send of an e-Mail to an action taker, a transmission to an operating device to change its behavior, etc. There is a wide range of such actions that over time are built out, put in a library, and routinely selected and used across a diverse range of business processes.

Of course, depending on the time horizon of our planning we will likely face changes in a very typically dynamic operating environment. We will discuss how this solution handles changes in inputs, constraints, and other factors later in the paper, but for now we have our core solution in place. That is, a dynamic ability to gather inputs, understand constraints, specify our goal function, determine optimizing actions, and orchestrate execution. The Agentic model allows us to sequentially add functionality, scale, and intelligence to successively improve our performance by continuously expanding our reach across an expanded solution space.

Step 5: Continuous Improvement of Business Performance and Smart Ops Execution

As we deploy our Agentic solution, we naturally want to ensure we can continuously improve our results by adapting to changes and new opportunities in our operating environment. Here we must in part rely on our business architects to be constantly assessing where our next sources of improvement may come from and then partner with the solution architects to bring to life the needed enhancements in our solution. If the core optimization techniques described above hold true, then we have a blueprint of where to look for opportunities to further improve our results. Examples include:

- seek out ever “smarter” agents which more accurately, quickly, and/or cheaply model, predict or optimize outcomes

- seek out agents which can acquire new, value-added data which improves predictability and richness of our understanding of the dynamic environment around us

- seek out agents that engage and interact with new customers, suppliers, and partners to enrich the universe of those we could do business with (dependent of course on finding new partners who possess better operations, supply, demand, or IP we can leverage to improve our business)

- seek out agents that can reach additional types of action takers such that our orchestration options are enriched

In summary, these agentic improvements and expansions serve to expand our solution space, improve the precision of the recommended actions, access and utilize new partners who bring enhanced capabilities, and activate decisions more effectively across our operating environment.

3. Business Transformation Considerations

With a core understanding of Smart Operations v2.0 in hand, we need to now step back and create the business context and motivations that validate its applicability to modern business situations. We can do so by cataloging a sampling of the core business challenges and opportunities seen today and exploring each from the point of view of how Smart Ops can help businesses successfully deal with those dynamics.

Sampling of Challenges

In the two decades since the original Smart Operations paper, there have been dramatic changes in the operating context for many businesses that have compounded typical challenges and caused a fundamental re-thinking of how a business understands its markets, customers, supply chains, competitors, and products. Here are a few examples and select examples of how businesses could successfully confront and respond to those challenges.

Business and Product Cycle Acceleration

Largely based on the rise of technology enabled / accelerated processes, many businesses have seen a significant shortening of business and product cycles. The rates of new product introduction have increased in many industries and suppliers to those producers have been pressed to speed up their innovation and delivery capabilities as a result. That in turn has put pressure on core business processes including new product development, supplier and material qualifications, contractual and regulatory compliance, and other key elements. To meet these demands businesses must find ways to accelerate their own execution in how they serve their Customers. A Smart Operations approach can drive substantial acceleration of these core New Product Introduction processes by leveraging agentified analytical capabilities that in turn depend on data acquisition/preparation agents needed to characterize materials, production processes, and other core R&D activities.

Supply Chain Complexity

Another critical element challenging modern businesses is the sharp increase in Supply Chain complexity. Collectively Supply Chains have become longer and more global and as a result more subject to international trade regimes, tariffs, geo-political risks, pandemic-induced disruptions, and a host of other challenges. To successfully respond to these challenges, Smart Operations can dramatically assist businesses both tactically and strategically. In short time horizons, classic demand/supply planning and execution activities can manage around sudden disruptions by automatically triggering trade-off analyses that re-optimize across a revised set of possible responses. For longer term planning, Smart Operations principles can be used that leverage increased prediction accuracy, supplier capability projections, and other derived insights to play out how markets are expected to evolve and how best to build out capabilities to serve those changes. Typically these decisions are closely tied to longer term investments like warehouse placement, factory scale-ups, and distribution agreements.

Geopolitical Risks & Trade Policies

Another dynamic that has caused considerable disruption to business activities is recent geopolitical developments which cause rapid and frequently unpredictable changes to the flows of trade and commerce. Wars, unchecked immigration, and protectionist trade policies can quickly disrupt carefully designed plans and networks of how a business executes its strategic plans. In such scenarios business ideally will simulate the causes and effects of possible actions and design products and services, supply chains, partnerships, and other components of their business plan to maximize resiliency. Smart Operations capabilities include sophisticated modeling of operating environments, trade policy scenarios, and governmental actions that can help businesses effectively explore their solution space both for short and long-term decision making. Developing a priori simulations that require sophisticated modeling of events and implications will help create models that can be continuously refined then introduced into core Smart Ops production environments to help improve recommendations generated by the system.

Access to Natural & Man-Made Resources / ESG Topics

Governments and NGOs are paying considerable attention to environmental and social issues that have broad impact on businesses and citizens alike. Energy consumption (driven by rapidly increasing AI deployment), clean water, clean air, and income inequality are just of the few of the top issues gaining substantial attention. Ideally, businesses need a flexible framework within which they can activate chosen strategies and guidelines that are aligned to their environmental and social principles. Setting those defined guidelines as constraints for decision-making ensures compliance because the business optimization analyses will always serve constraints first in crafting the best possible business outcome. By actively modeling such environmental and social constraints and making those a part of the problem formulation, businesses using Smart Operations approaches can directly and visibly align their operations to their stated ESG goals. Internally there are also opportunities to model, for example, the compute-driven consumption of energy and water in datacenters that power Smart Operations execution. It makes sense that similar to how we may model constraints on business activities we can also model constraints in our compute environments to meet such ESG objectives.

Sampling of Opportunities

On the flip side of challenges to business execution there are also emerging opportunities that business architects can take advantage of as they expand and extend their businesses. Here are a few and how Smart Operations can assist in deploying intelligent strategies to take advantage of each.

Sovereign Interests

A recent development that presents interesting opportunities for business architects is an increased awareness on the part of individual countries of the role they do or could play in the conduct of international commerce. Establishing sovereign wealth funds who invest in local or foreign opportunities, creation of free trade zones, creation of low tax opportunities or investment tax credits, and similar strategies are helping countries build sustainable economic and social growth vehicles for their citizens. By evaluating these trends, it may be advantageous for businesses to identify, model, and simulate various country specific situations which allows the Smart Ops solution to determine the most advantageous ways to build out and scale their firms. By dynamically trading off alternatives and optimizing across the set of feasible solutions, we can evaluate a multitude of different combinations virtually and quickly. As we saw earlier, initial simulations can help identify and validate opportunities with a later introduction of such models into the production environment where these models determine and orchestrate specific actionable recommendations.

AI/Technology

It is likely obvious and in fact the heart of this paper that AI and more broadly digital technology can and will play a major role in helping business identify and activate the best strategies and tactics to deliver on business goals. The emergence of sophisticated data capture, modeling, prediction, simulation, and optimization techniques and platforms is unlocking entirely new ways for business leaders and process owners to conceive, build, and operate a business. It is of course incumbent on these leaders to set robust vision, empower individuals, provide resources, and hold people accountable that will enable success from the deployment of new technology. As opposed to two decades ago, the emerging capabilities to process fantastically large datasets, extract useful insights from that data, model the real-world around us, instantly communicate around the world, engage humans deeply with the technology environment, and measure with precision the results of actions taken present a compelling opportunity for technology to fulfill its potential as a value-creation lever.

Access to Diverse, Deep, and Valuable Data

A final new opportunity worth mentioning is the unprecedented access to data of all types, volumes, and locations. As discussed earlier, the emergence of diverse and widely deployed sensors which can sense and collect a wide range of data is helping us better understand our world and the interactions between diverse actors. Having increasingly timely, granular, and valid datasets dramatically improves the confidence we have in the models we rely on to characterize the behaviors or intentions of people, machines, systems, governments, nature, etc. Our ability to capture and process this data has created completely new levels of understanding of our operating environment and we see a constant stream of new data sources being introduced. We must of course carefully weigh the costs of acquiring and using these new sources. Fortunately, our optimization-based approach within Smart Operations provides a direct evaluation framework of how a revised and augmented set of models can produce ever more valuable outcomes allowing us to compare and ensure that incremental value exceeds incremental cost.

4. Core Transformation Strategies

With the context of increasingly important business environment considerations established, we must face squarely into the challenges of designing and deploying a transformative strategy that is embraced and accelerated across the business. As IT has painfully learned over decades of experience, great technology will never reach its potential unless we position it strategically with senior leaders, build a sound business case for the financial community, design a change management strategy that engages every level of the organization, construct a highly credible execution plan recognizing internal capabilities/deficiencies, and effectively communicate with stakeholders throughout. To that end let’s explore a methodology that can be used to develop a successful transformation roadmap for the scope and scale of a Smart Operations transformation.

Specify Financial Objectives

Clearly codifying the financial objectives for the firm is a critical first step in any transformation. Here we are using market-based outcomes to specify the level of performance that investors and senior leaders will find acceptable. The selection of targets, including both type and magnitude, will establish important boundaries and areas of focus for the subsequent design and intensity of investment initiatives that will be required for success. Most often these are captured as revenue, operating margin, or working capital, but increasingly other metrics are also being used to indicate capital efficiency, environmental impact, or other indicators of success. It is also crucial to indicate the timeframe for achievement of each goal to ensure required levels of intensity are well understood. Of note, these objectives as well as others throughout the business may require iteration as we examine the fundamental opportunities and constraints the business may encounter. Ultimately having clear targets as a measure of success will help establish proper accountability and a shared commitment to achieving the desired outcomes.

Map Business Strategy

Once clear financial objectives have been codified, it is necessary to develop and pressure test relevant strategies that will be employed to deliver the targeted outcomes. Typically, these strategies are a combination of financial (how we will secure investments), operational (where we will make product), organizational (how many employees versus contractors we will hire), and so on. These strategies begin to decompose targeted financial outcomes into actionable themes to be undertaken by various leaders across the organization. It is worth noting that even at this stage the business architect has the opportunity to begin shaping an understanding of the core capabilities and their respective measures of excellence that will be required to succeed. It is also beneficial at this stage to engage a wide range of experts and experience to evaluate, question, iterate, and improve these core strategies to ensure their robustness in real-life application.

Core Competencies

Once core strategies are defined and validated the business architect and others must catalog the core competencies and level of proficiency required to successfully deliver the requisite strategies. This is often a very difficult exercise as firms frequently lack a sound methodology to self-assess each competency, but the exercise helps a firm honestly baseline where and how it wins versus simply being a qualified contender. Core competencies are usually higher-level constructs (e.g., curating customer experience, providing market-leading innovation), but definitively capture the essence of who the firm is, how it is perceived in the market, and what it can rely on to differentiate itself. Having a good grasp of the core competencies required to power the chosen strategies provides clarity of the key themes around which follow-on improvement activities can be identified and pursued.

Map existing Application & Analytics Landscape

Taking a turn toward the more technical elements of the transformation, a key step after core competency assessment is to map and profile the existing Application and Analytics landscape in the company. As the repository of digitally based competencies, we must understand our current digital competencies and capabilities to collect and process data, support intelligent decision-making, and execute proscribed actions. There may well be remediation activities in any of these areas that are a precursor to more sophisticated pursuits in the march toward a smart operation. Any such improvements will necessarily have to be catalogued, funded, assigned, and executed in turn to ensure readiness of that capability to contribute to higher levels of achievement.

Map/Cleanse Enterprise Data

One of the newest and most challenging elements of a Smart Operations transformation is the mapping, cleansing, and overall preparation of Enterprise data. With the exception of a few forward-thinking businesses, most companies have not actively and carefully managed and governed their data over the last decade. Combining a lack attention in terms of governance with an explosion in data generation and capture has created a huge headache and barrier for companies looking to utilize the newly AI inspired analytical techniques. Competing databases that have alternate definitions of product, customer, defect, order, etc. all conspire to confuse and confound attempts at robust analytical and modeling pursuits. Such competing definitions will ultimately degrade efforts to fully leverage such data in the creation of high value information, knowledge, and insights. Many firms even set aside / delay the start of their transformation efforts until they get their data in order.

Within the context of a Smart Operations transformation, it is possible to focus on an initial slice of the firm’s total data holdings as long as it is clear that everything relevant to the initial improvement area is in the scope of the initial data cleansing. It is crucial that a data management plan is built holistically and target constructs for clean data structures are established early on and rigorously maintained thereafter.

Baseline Organizational and People Capabilities

As a deeper dive into the core competencies discussed above, it is now necessary to profile the individual capabilities from which higher-level competencies are composed. Here we are drilling into the details of business processes, people and skills, business partners, and others to capture and document their relative functionality, maturity, capacity, and scalability. These capabilities serve as the building blocks of a business and are often improvable components of the overall transformation plan. On the journey from financial outcomes to strategies to competencies to capabilities, we begin to develop a mapping of needs and the target levels of performance versus what we currently have in place. Fortunately, there is a rich set of capability building methods available, ranging from people training, process assessment and improvement, and system deployment. It all comes down to improving the next most important thing, in an aligned and most cost-effective fashion, and ensuring those improvements are fully adopted and leveraged in the context of higher-level requirements.

Business Process Design & Improvement

As we complete the decomposition of what we want and what we have, we must transition to improving or building capabilities that enable us to achieve higher level strategies and outcomes. As discussed earlier, we define the business process as our core fundamental building block of business activity and capability. Using the approach outlined earlier we need to establish a definitive understanding of how our business processes work, their ultimate capability (entitlement), and their current performance levels. Assessing those elements tells us if we can improve or must re-design our way to acceptable levels of performance. Similar to the discussion in the Data section, it is acceptable to initially focus on one or perhaps a small number of important processes to improve. That is even advisable in the early stages of a broad-based transformation such as Smart Operations to ensure the team stays focused and accountable to delivering defined improvements quickly and with a suitable ROI.

As this step progresses, we become increasingly equipped to lay out the various people, process, and technology improvements that are required to progress our capability to the target level of performance.

Specify a Process Improvement Plan

With a clearer understanding of the process improvements required to attain a target level of performance, we can develop a specific plan to smartly attack and sequentially improve the elements of the process that are underperforming. Using the techniques described earlier we profile tasks by performance and complexity, prioritize and categorize improvement actions and document the composition of the specific improvement plan. We can then launch process improvement actions natively or dive into lower-level elements of each task as covered in the next two sections.

Specify a People Improvement Plan

Frequently we see cases where new or newly assigned employees are ill-equipped for success in a given role. This is often caused by a lack of training, knowledge transfer, suitable tools, or a number of other root causes. As we evaluate tactics to improve various tasks we should carefully assess if training or other human-centric methods are the most suitable avenue to drive the needed improvement. As we profile across multiple tasks, we may see key themes we could address at scale (such as a group training class) or realize individual attention is a better choice. Carefully collecting, aggregating, analyzing, and preparing such an improvement plan will pay dividends both in terms of process performance but also in terms of personal commitment to success, productivity, and loyalty to the company.

Specify a Technology Improvement Plan

Next, and in a manner similar to the People improvement plan, we must develop a technology improvement plan. Drawing again from an earlier section, the use of core automation techniques and/or more sophisticated agents and agentic technologies provide a very rich set of options for the process designer to leverage as they balance cost, scalability, reliability, adaptability, etc. in pursuit of target level performance. Fortunately, these technologies are improving both in performance and price at a rapid rate which provides tremendous flexibility for the designer. The earlier section lays out a multi-stage process for transforming key processes to very high levels of performance by using increasingly sophisticated techniques.

Design / Execute a robust Communications Plan

Finally, it would be a mistake to not discuss the importance of a robust Communications Plan regarding the intent, timing, approach, expectations, and results of our transformation efforts with the entire organization. Nothing will derail a strategic initiative such as this quicker than for information gaps to exist across the organization. Without clear and honest communications shared throughout the organization, you will soon see fissures forming: front-line employees will see this program as a mass layoff strategy, technologists will see this as a chance to run a big tech program (or a takeover by some outside consulting firm), and so on. Nothing beats the CEO or Transformation Leader delivering a series of all-hands meetings where he/she delivers a clear accounting of what, why, when, how and so forth to the organization including a commitment to come back and report on progress, lessons learned, success stories, failures and corrections, etc. Being honest with everyone will create the best chance of success and promote robust and badly needed engagement throughout the organization.

5. Key Constituencies

I see five key constituencies each playing an integral role in conceiving, designing, building, deploying, and adopting this vision and each has specific contributions that will be needed to accomplish this transformation. Each in turn will also receive specific benefits that reinforce its willingness to contribute actively toward reaching target performance. Here is a summary of each constituency, its benefits, and contributions. Note that there is an added Private Equity twist to this accounting to incorporate the added players that are involved with companies in whom Private Equity has invested.

Senior Business Leadership

Senior leadership of a company is ultimately tasked with setting vision, developing strategies, allocating resources and being accountable for delivering the target financial outcomes of the firm. As they perform these various duties, they are constantly scanning the horizon for emerging trends, new competitors, paradigm shifts in their industry, and a host of other strategic influences. What many senior leadership teams seek are strategies and investments that build capabilities which have the flexibility and adaptability to adjust to the constant strategic and tactical course corrections needed to maintain competitiveness without wholesale “re-investment.” As such, senior leaders who can clearly convey their vision and strategic intent to those who will build and operate the business, will create a much higher chance of long term success because the foundation of the firm will have been built with these principles clearly in mind.

For this very reason, senior leaders will play a critical role in setting the context for a Smart Operations style transformation. Clearly laying out the company’s vision and strategies will provide the Smart Ops architects with critical insights into how best to partition key business capabilities into adaptable, flexible, and scalable constructs that can be more easily adapted, re-configured, and re-deployed to implement the ongoing adjustments needed to respond to changing conditions.

Senior leadership must also play a leading role in creating the right sponsorship, governance, and communications for such a transformational journey. Establishing clear expectations, rules-of the road, performance measurement guidelines, etc. will be crucial to ensure the right feedback signals reach senior leaders and enable sustained support for the program.

Finally, senior leadership will be asked to provide the right financial and people resources to lead and deliver the transformation program. Selecting the right sponsor is a critical step in the transformation journey. Naming a leader who balances strong communications skills, program leadership disciplines, motivational practices, and possesses the instincts to protect a team during challenging periods, etc. may be one of the most critical elements of success.

The return on investment for the senior leadership team is a business built ready for the challenges ahead. The ability to rapidly re-configure elements of the business and operating model, dynamically respond to disruptions in Supply Chain, Staffing, and Competitive actions, and have truly deep insights into the inner workings of key business activities will provide a truly robust, differentiated business that is built to last.

Deal Team & Investment Professionals

In scenarios where a Private Equity or other Business Ownership structure is in place, we must anticipate and embrace the role of these owners and their expectation for improvements in Enterprise Value. Particularly in the case of Private Equity, we must also anticipate the dynamics around the target holding period and ensure our transformation strategy is accretive to and not dilutive of the core selling proposition for the company. As such it is important to engage the Deal Team upfront and architect a transformation strategy that is relatively immune to the potential early or late sale of the company. This in turn requires a thoughtful strategic transformation journey map that at any point can be successfully marketed to a potential buyer of the business.

As discussed in the Smart Ops section, we foresee the potential for a compelling telling of the transformation story at each step of the journey. Even if an early sale is contemplated, the ability to tell a cohesive story about a process-based, sequentially sensible improvement strategy with incremental investments and returns is a compelling one. Characterizing progress to date, specific initiatives in flight, and next steps all with a strong alignment to core strategies and ultimately financial outcomes, should be seen as a benefit and not a risk by potential buyers.

At the same time, a transformative journey such as Smart Operations will require engagement, patience, potentially some additional capital and certainly sustained commitment and encouragement from the Deal Team. For a management team knowing they have a committed Deal Team behind them will inspire forward-thinking, intelligent risk-taking, and a strong desire to deliver.

Functional Leaders & Operating Partners

Functional Leaders (and Operating Partners if again Private Equity is involved) are one of the most critical members of the transformation team. In most situations these leaders are the critical linkage from Senior executives who set strategy and allocate resources to the front-line employees who execute the business daily. Along the way these functional leaders are responsible for the design and delivery of the core competencies of the business. They represent vast experience and expertise, are responsible for talent development, and are specifically held accountable for results in their operating areas.

In the context of a Smart Operations transformation, these functional leaders will be a linchpin of success at the very core of the program. They will serve as the first line translators of targeted financial outcomes to robust business strategies. Next, they will task their leadership teams to take those strategies further down to core competencies and capabilities from which they will identify required improvements. They will also assign accountable staff to deliver on actions they have reviewed and approved. Given this range of critical responsibilities, the Transformation Program Leadership team is well advised to build and maintain very robust relationships with this core group of individuals. It is not at all uncommon for a leading member of this group to specifically be selected to lead such a strategic transformation program for the company. Having deep operational and leadership skills in such a position should be seen as a great advantage for the program.

IT Team

As keepers of the technology environment in the business, the IT Team has the responsibility to ensure that all deployed technology meets functional needs, maintains operational security, exhibits availability aligned to business operations, and is highly cost effective. That is a tall order for any IT organization let alone one also attempting to engineer a highly transformative strategy. As the Program unfolds, IT must effectively leverage its internal relationships, existing trust across the business, and eye for how best technology meets key business needs to constantly evaluate and ensure that each phase of the transformative program maintains alignment to the core principles and requirements of the business.

It is likely the IT team already uses a set of Managed Services and Security Services providers (MSPs, MSSPs) in the delivery of its services to the broader organization. The accumulated experience in the selection, management, and guidance of those organizations must be directly leveraged when possibly adding new Partners to help drive the Smart Operations journey. IT will play a leading role in stitching together such a robust ecosystem of Partners who must seamlessly work together to design and build the Smart Ops capabilities and successfully deploy those into the business. As such, IT must identify and assign its strongest leaders into key Program roles and rely on its experience and understanding of key business drivers to help shape and guide those new Partners. If done well, the Smart Operations-inspired transformation can take IT to new levels of recognized contribution to the strategic success of the company and, most urgently, rightfully position digitally-enabled solutions as another key value creation lever for business leaders as they devise strategy, solve critical business problems, and capture new opportunities.

Technology & Service Providers

Technology and Service providers will be a critical component of the Program team for the Smart Operations journey precisely because they offer the expertise, scale, and capacity to augment key missing capabilities within the business. Ideally these Service Providers help the Program Team accelerate key decisions based on their broader market knowledge, reduce deployment errors given their deep implementation history, and create operating leverage for IT by bringing their own developed IP and best practices. A deeper examination of the many roles Partners will be needed for is detailed below but here we will simply summarize what is needed and what is gained by Partners invited into the Program.

There are three specific competency areas that must be robustly present in the Smart Operations transformation and the first centers on the ability of the Program Team to understand and address critical strategic, financial, and operational goals of the Enterprise. Within this competency we need both an element of management consulting (understanding, advising, and aligning to core strategies) as well as value estimation and realization. While the former ensures the program team is aligned to and addressing key strategic needs, the latter helps the team properly estimate the quantity of and how best validate the realized level of benefits derived from the program.

The second major competency area is Program Management. The Partner must excel at structuring and leading a complex, multi-faceted program that balances required technology deployment with an acceptable pace of business and people change as well as business resources and funding made available. A second key competency required is broadly “Change Management.” Change Management practices and expertise will ensure that changes in both Product / Service delivery as well as internal business processes are robust and well managed.

A final area of required competency is core technology implementation. It starts with employing robust frameworks and experienced staff at devising the core solution architecture and ensuring a balance of flexibility and adaptability across the architecture. Finally, the Partner must also excel at platform selection, implementation, and operationalization. Ideally the Partner demonstrates robust anticipation of evolving technology and best positions each new technology introduction to play its designated role.

6. The Future of Work

The potential impact on the nature of work and in turn the workforce of an Enterprise is perhaps one of the most interesting and consequential elements of this paper. With the rise of new AI-based techniques and platforms there is no shortage of predictions as to exactly what the ultimate impact on Enterprise staff will be. Today we see prognostications ranging from a complete wipe-out of low level and even some higher-level jobs, as AI sophistication grows into reliably performing these roles (especially in the Generative AI arena). Others argue that humans will always play a vital role at contributing the goal setting, ethical, moral, and related principles that can and should guide organizations. Over the last few decades, we have seen the constant march of new technology and generally results have been mixed at fully thinking through and properly positioning our people and people management disciplines to best balance the consequences and potential of technology adoption.

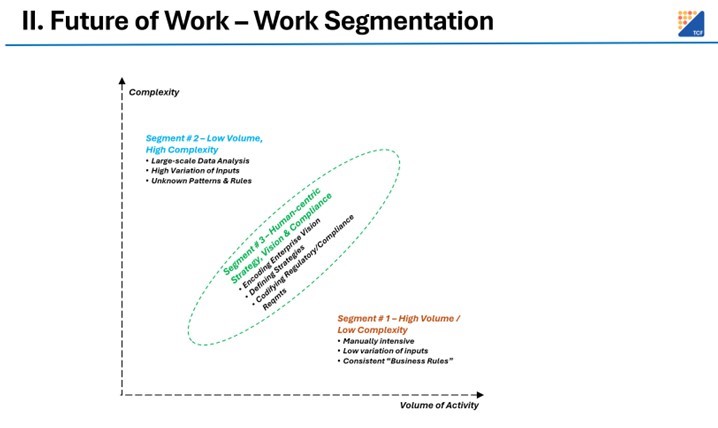

The position taken in the Smart Ops vision is a balanced perspective where we segment the duties within an organization and place those responsibilities where they are best served. While the goal of an organization is to succeed in its core mission, the broader individual and societal perspectives merit significant consideration. The following framework attempts to provide a balanced approach to these competing dynamics. Please refer to Figure 2 as we explore these various Work Segments.

Figure 2. The Future of Work – Work Segmentation

Work Segment # 1 – High Volume, Low Complexity Tasks

We profile activities into this segment that are characterized by broadly routine high volume but low complexity tasks. These tasks have traditionally been handled by people, often in front line roles, where experience and repetition have built capability. Given these more routinized tasks where inputs, work activities, and outputs exhibit relatively low variability, they are traditionally the first targets for classic automation efforts. As robotic process automation and similar technologies have evolved over the last few years, we have seen a much stronger blend of machine-driven execution taking at least the lowest complexity tasks with triaged and more difficult cases being routed to experienced human staff. As generative AI capabilities have exploded in the last 24 months, we are seeing an expansion of front-line tasks that can be handled by trained AI Agents who are modeled (trained) across countless prior transactions and activities to effectively handle the majority of more complex cases. While it makes sense to retain some human participation in this segment, largely to oversee quality control and model ongoing improvements in how machines interact with human customers, the bulk of activities in this segment will likely go largely in the direction of Agents sequenced by core business process flows.

Work Segment # 2 – Low Volume, High Complexity Tasks

The tasks that populate this segment of work are characterized by high complexity with widely varying inputs and outputs. These are often analytically intensive activities, given the explosion in data volumes has effectively taken this work beyond the capacity of humans to adequately perform. Tasks in this segment include forecasting demand across years of sales history, extracting key themes and insights across volumes of documents, and optimizing performance across multiple operating dimensions. The advent of machine learning and other analytical techniques have dramatically improved the speed and quality of such work, and practically speaking, lands squarely in the domain of machine-led processing. As echoed in Segment # 1, the expectation is there will still be a core set of humans involved in this segment’s activities, largely to help guide and shape deep analytical modeling and techniques as well as helping to identify, source, and engage newly available data sources. Virtually everyone sees these capabilities continuing to rapidly expand driven by ever more robust analytical and compute capabilities available for consistently lower cost. The strategic role of this segment should absolutely grow substantially and is the cornerstone of Smart Operations, that is, the dynamic and rapid response to ever changing internal and external conditions all projected and guided by an optimizing engine.

Work Segment # 3 – Human-centric Vision, Strategy, & Compliance

This element could be considered the overall “glue” of the entire solution. Most AI “experts” still feel that true intelligence is still far off in time but one could argue we may never be completely comfortable turning over the running of a business to a machine. Having a critical element of humanity retains the intangible and often very difficult to model behaviors, compassion, and sense of community that people bring to their jobs every day. What if we haven’t yet perfectly modeled a machine to always do the “right thing”? Retaining the human element feels not only responsible but practical – always present to make a final determination when our algorithms have never seen a particular situation or can’t resolve every situation within its instructed parameters.

In this element we see humans taking the lead role at setting organizational vision, validating acceptable strategies, as well as determining the social and environmental principles and guidelines that are “right” for the company. Those guidelines and principles need to be properly characterized and structured for “machine consumption.” and the more unique or first-of-a-kind situation we must anticipate, the more human reasoning and judgement will be crucial to proper structuring. We also need humans as the ultimate feedback loop to deal with the one-off, never-seen-before conditions that could cause unresolvable conflicts in a machine-only environment.

Caution – Don’t lose your best Future Workforce